Hello! This month’s (belated) email is about some of the binaries I’ve undone and re-encountered in my life around gender and sexuality. The experiences I write about in this email really re-shaped my brain, and are in many ways the origin of my work on nonbinary approaches as a way of moving through and around the compressions of dominant culture.

And, this email is far from perfect, or fixed — I still am not totally sure it covers everything (or most) of what I want to say, and there’s a chance that I’ll wake up tomorrow with different takes, more or less nuance, a sentence I wish I had shared with you. I hope that whatever friction you find here, you’ll share in the comments on this post, so we can continue the process of unraveling this particular binary together.

It has been a funny thing writing about queerness during pride month — a time that both celebrates so much expansion of sexuality and gender, and which also exposes so many binaries in the ways we think about and approach sexuality, normativity, and difference. It took me most of this month to write this email, and there’s a lot here — as always, please take your time and go as slowly as you need. If anything comes up for you as you read, I’d love to hear it. <3

sending much queer love,

Kali

when the good side of the binary feels bad

When I was in my early twenties, twelve-ish years ago now, I remember walking around Bloomingdale, the neighborhood in DC that my then-partner lived in. If you’ve ever been there, you know it’s a small part of the city, probably covering an area of six by ten blocks. It falls between two major avenues, which run diagonal to everything else in DC, so it looks less like a typical city grid and more like a half-open accordion.

I walked the sidewalks on those truncated blocks like a labyrinth for weeks, trying to puzzle out a decision whose answer I had already begun to live out, but/and that felt important to name to myself. I was weighing two options — whether to say, once and for all, that I was going to clearly choose to live the life that I had already begun living, one where my queerness had room to breathe; one guided by, or at least not fearful of, my pleasure and the pleasure of others; or whether I was going to go back into the closet, return to pretending to be straight, and live the life I’d always thought I’d have, and the one my family and church community had imagined for me growing up — marriage, motherhood, church on Sunday.

Like so many people, I had grown up believing that heaven and hell were real, and that if I lived the life here on earth that I found so much joy and aliveness and relief in, that I’d suffer for it, forever, once I’d died. And that if I fit myself back into the particular narrow path I’d been born into, I’d be rewarded afterwards with a whole lot of non-suffering and ecstatic worshipping for forever. It felt like a truly impossible decision to make consciously, so I walked instead, and felt the weight of the two lives I was carrying.

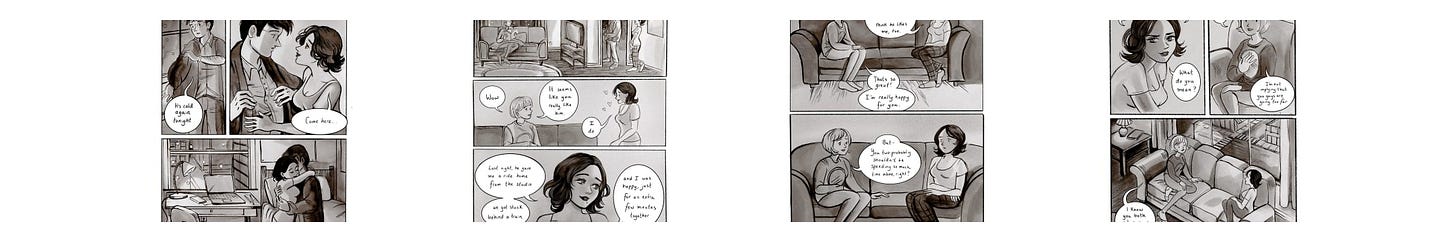

I’ve really been loving reading Stephanie Stalvey’s comic Pure, which captures a lot of the conundrums that come up for people wondering how to live within the confines of conservative christianity.

unclear queerness

Much of the narrative around queerness, and closeted queerness in particular, can make it sound like queer people know we’re gay from an early age, and that the major need is for spaces where we can express that part of ourselves. And while I know that to be true for many people, one way it can play into the straight/queer binary is by drawing a line between two groups of people and saying that they’re distinct, different and non-overlapping. You either know, and are queer, or don’t, and are straight.

This functions, in my experience, more to protect straightness from any kind of scrutiny than it does anything else. Because if you can grow up having no clue that your sexuality or gender is different from what was presented to you/assumed by the people around you, or you maybe never have a clear sense of being different, just a kind of vague unease, or your sense of yourself doesn't really match up in any way with what the story of being queer or coming out looks like, and yet you can still be queer, it blurs any clear line between these supposedly distinct categories of straight/queer. It opens the possibility that the thing we call heterosexuality is constructed, and not just innate. That there are many ways into, perhaps infinite expressions of, what we call queerness, and that the borders of each of these categories are less defined than dominant culture would have us believe.

Queerness was never clear for me, at least at first. I found myself in queerness slowly, or maybe my queerness emerged slowly, my body understanding before my mind felt safe to do so. I learned I was queer by following what felt good for and in my body, all while being terrified that the all-seeing deity would notice what I was doing before I had a chance to actually live it.

After a couple of months of walking, I remember telling myself, I think I just have to trust that this life that feels so true for me can’t be all the things I’ve been taught — that life isn't some cosmic, ever-present test of correct behavior, or of the right way to do things. That the way my body lit up in and around sex and other physical pleasure was just an experience of being human, not a terrifying temptation into damnation.

I remember asking, Why would life be set up so punitively? It doesn’t make any sense. And because the religion I grew up in relied heavily on things not making sense, since human logic was so fallible in the face of omnipotent divine command, I remember thinking, I think I just have to trust that I can be both queer and loved. I felt both a kind of relief and terror of throwing myself on the mercy of whoever was in charge of meting out judgments at the end of everything.

As anyone who has had an experience of this kind can attest, things only got more complicated from there.

the (terrifying) soup of possibility

Having leaped out of the category I had lived within for so long, I realized that I had inadvertently undone the whole logic of the binary: if straight was (as I’d been taught) good, happy, correct, and right, and queer was sinful, suffering, bad, and wrong, and yet as a queer person I existed and felt joy and pleasure and connection, my experience undid the whole damn thing.

There’s a way that letting go of one side of a binary can feel like letting go of the ground itself — if everything I thought I knew about not being straight was not true, then what? If everything I thought I knew about myself was also not true, or was unravel-able with enough questioning, where would be the end of that? Would I ever have a solid sense of myself again? Was that even possible? If I said I was queer, which according to the logic of the binary, was a rejection of the beliefs I grew up with, what did that actually mean?

Bolstered by the thrill and terror of having acknowledged to myself that I was no longer heading through life as it had been laid out for me, I found myself questioning everything: how I held myself, walked, talked, dressed, how the people around me saw or didn’t see me, how I talked about who I was and who I was attracted to, how I knew what I wanted or didn’t want, on and on. I had so many questions about what life could look like now — it felt a little like getting a single tightrope-walking lesson, and then being handed a balance pole and told, “good luck!” as I was pushed out onto a wire.

what the other side of the binary offers

Into this soup of questions and un-making, and so much possible meaning that everything felt meaningless, queerness as an identity oppositional to heteronormativity — with a particular set of markers, behaviors, and culture — arrived as a kind of flotation device. A space I could find myself in, learn to inhabit, and become legible or visible to myself and other people in a particular way.

For me, queer culture became a place to regroup and understand myself. It was comforting to find a place, and people, with stories and knowledge and wisdom that I felt like I was missing, to help me find the ground again. Queer community offers so many of us, regardless of our gender and sexual expressions, a space to feel at home, to experiment, to try things out, to grieve and rage, and find ways of living that give parts of us, or all of us, a space to breathe and rest and emerge. Having a bounded space to regroup and re-ground is perhaps a necessary part of undoing the binary without totally losing your sense of self.

I grew up steeped in the belief that queer people were unnatural, not right, going to hell. And it was clear at a very early age that parts of myself should be repressed for my own safety, in order to be accepted and loved. And when I no longer had to repress those parts of me, I found myself very, very angry, and at times bitterly contemptuous of the culture and people I grew up with and under. And that anger aligned so well with a kind of opposition and disdain and judgment of christianity, and heterosexuality, in a way that kind of grew and grew to fill my own sense of queerness as mostly oppositional to these ways of being and seeing the world.

It’s not that I think that defiant, angry responses to repression are in themselves bad or wrong. I am so grateful for the space I have had to acknowledge and grieve and rage at my experience at the hands of well-meaning, terrified people who found a kind of safety in the idea that to be a good person means to destroy any kind of non-normative (normative, of course being cis-het, conservative, capitalist, white supremacist, ableist) expression or identity. But I increasingly found myself exhausted by feeling like I was holding on to the other side of the rope in a cultural tug of war.

beyond the binary of queerness

I have written and re-written this part of this month’s email probably ten times — it’s the reason you’re receiving it in early July and not June. Part of the trickiness for me is how and where to combine my personal experience of queerness and nonbinarity with notes on binaries, which are fractal in structure (functioning essentially the same no matter what scale you use to consider them). But I think, after so many drafts, what I want to say is this:

Finding ourselves on the opposite side of a binary - the “bad” side, and delving into the intricacies and subversions and deviations of it, is one way to work with binaries. It’s a practice that queer people know well, the celebration and reclaiming of “bad” as something to be embraced and inhabited. It’s where camp and kink and smut (and sometimes drag) live.

And, too — I think it’s important to remember to inhabit this side of the binary playfully, as a performance, rather than as something true, the other “half” of human sexuality. Because while the construction of the straight/queer binary seems to acknowledge that there is more to life than just one way of being, what it actually does is exaggerate the importance of straightness — gives it more room, more legitimacy, than I think we need to pay it. This binary is constructed to do certain things — to support a patriarchal view of the world, to categorize people, to disappear or contain particular ways of being. And queerness, by definition, is uncontainable — full of all kinds of structures and ways of being. Queerness, to me, is a way of describing the planet we live on, where beings merge and pulse and entwine and evolve and change, where decomposition and recomposition are the same process, where endings and boundaries move and morph over time and are never fixed. A process of unfolding, of not-knowing, of encountering and re-encountering.

There’s this Ursula K. Le Guin quote from the book The Left Hand of Darkness that I really love:

“To oppose something is to maintain it. They say here ‘all roads lead to Mishnory.’ To be sure, if you turn your back on Mishnory and walk away from it, you are still on the Mishnory road…You must go somewhere else; you must have another goal; then you walk a different road.”

— The Left Hand of Darkness

I’m not saying that we don’t need hearty opposition to policies and systems that seek to erase queer folks, and trans people in particular. Opposition and defiance keep people alive. But/and: I hope we can remember that our opposition is a tactic, not an identity bounded by the other side of the binary. That while the straight/queer binary runs so much of all of our lives, it is made up. Just one tiny road out of so many possible ways each and all of us can go. And I hope that we can hold both the need for resistance to fucked up things like transphobic legislation and for a more expansive model of what is possible for all of us. Opposition makes space, but/and nonbinary friction creates the possibility of unraveling the whole logic.

friction as nonbinary becoming

I think for me I have come to understand this entire process as a part of nonbinary approaches. We unravel part of the sweater and all of a sudden it feels like there’s no ground, nothing is solid. We come face to face with the reality underlying all of the binary construction, which is that so much of our culture and society and ways of being are just made up — that we can do things differently, and that what holds them up as real is mostly our collective belief in them, rather than any kind of external mirror or modeling on the planet around us. I think that in some cases, choosing to keep or inhabit either side of the binary is a kind of rest stop or respite in the soup of meaning-making.

What I would posit is, though, that even though letting go of the binary can feel like we move into a new space of meaninglessness and chaos, that logic is in itself another binary, where binaries equal order, and nonbinary approaches are structureless chaos. When actually, nonbinary approaches are about noticing the multiplicity of structures available to us — from the branching networks of mycelium, to the dance of rivers across the landscape, to the complex patterns of starlings, to the subtleties and obviousnesses of our collective gender expressions.

In nonbinary approaches we learn that meaning-making is a thing that all of us are doing all of the time, that we can choose, or listen for, or notice the structure that feels right for us in the moment as it emerges. That we aren’t bound to things staying fixed and the same forever. It’s an approach that’s less like realizing that nothing is real, and more like finding our place in the family of things, where everything is real, all together, all at once.

I still have binary approaches in me. I still feel so much rage at the ways I didn’t feel safe to express parts of myself as a kid, and how that impacts me as an adult trying to build beautiful partnerships in emergent ways. In many ways I’m still holding fiercely to my defiant opposition to the straight-laced christians I grew up with. And yet, I understand that all of these experiences make up me, in all my contradictions and messiness and everything-ness. I contain in me, too, in my cellular and language-based memory, the experiences of my ancestors, my parents, my larger biological and chosen family, and all of the places they and I have lived, and immersed ourselves into.

I have learned, in these twelve or so years, to hold space for the capacity to be surprised, to not know what is going on, and to understand that making, unmaking, and re-making meaning of our lives is a deeply human trait.

I had to have unexpected surgery this past December for endometriosis, and in the process had 3/4 of one of my ovaries removed, and I’m surprised at how different I feel these days — how my body and my gender feel like they’re taking a breath in sync together. I didn’t think I needed a body change to feel more nonbinary, but/and now that it’s here, I feel grateful — for these new experiences, for the ways I feel more connected to my younger self and my ancestors, for the ways living and being alive can still surprise me and ask me to question and re-evaluate, re-make my sense of myself.

If I had to define queerness for me now, I would say it is a process of noticing and learning and appreciating what about myself that is growing, and changing and shifting, especially what in me is oriented towards pleasure, joy, juiciness, laughter, connection, friction, staying together and staying with, no matter what. Queerness makes space for all of the parts of us, for all the ways we are and can be.

I hope, wherever and whatever you find yourself making and unmaking these days, that you can hold space for all of the contradiction and messiness and angst of being a human, and the ways each and all of us are still learning about all of the expressions that people (including you) can live into. This song reminds me of that possibility.